It has been a decade since the Public Sector Accounting Board (PSAB) required local governments to incorporate capital assets into financial statements with PS 3150. Since then, local governments have improved their capacity to decrease their respective infrastructure deficits and better plan for asset management activities. The adoption of PS 3150, in combination with Federal Gas Tax requirements for local governments to develop Asset Management Plans, has allowed local governments to better understand their annual infrastructure funding requirements and alleviate sudden emergency expenditures when assets require replacement or significant maintenance. These asset management planning activities have improved outcomes for many local governments; however, the standard was designed to help local governments replace or maintain assets that are to remain in service.

For those assets that cannot remain in service or have additional costs when they reach the end of their useful life, local governments in Canada have, by and large, addressed and acknowledged those costs only at the time of the asset’s retirement. An example of such cost would be the environmental actions required to close a landfill once it has reached the end of its useful life. In some cases, this may require that the local government install a final cover and vegetation in place of the retired landfill regardless of the site’s use, based on previous contractual agreements. These required activities may cost hundreds of thousands of dollars that the local government had not previously planned for. Unexpected activities such as these can increase the constraints on local government to deliver other services appropriately.

Asset Retirement Obligations

To alleviate the potential issue of sudden or ineffectively planned liability expenditures related to the retirement of an asset, the Public Sector Accounting Board approved recommendations for the adoption of an accounting standard specific to Asset Retirement Obligations (AROs). As of April 1, 2021, PS 3280 requires all government entities to account for any Asset Retirement Costs (ARCs) at the time of construction or acquisition of the asset and to add those costs to the value of the asset within the Tangible Capital Asset (TCA) register. The ARCs also must be accounted for retroactively, so any assets the local government currently owns that have an ARO will require to have those costs calculated and added to the TCA register.

This new section is the only Asset Retirement Obligations standard to explicitly define buildings with asbestos as in scope. Governments should have a full understanding about the potential retirement obligations. For Local governments, the major level-of-effort for applying AROs to existing assets-in-use (within the TCA register) may include buildings, underground pipes, and landfills.

Key considerations:

- What judgment should be applied in determining the extent of AROs, and how should these be measured based on applicable regulations/legislation and/or agreements?

- What are the auditor’s expectations with respect to AROs, and particularly of work required for buildings with asbestos?

- PS 3280 rescinds the guidance on accounting for solid waste landfill closure obligations and rolls it into the new section. How do governments go about transitioning existing landfill accounting?

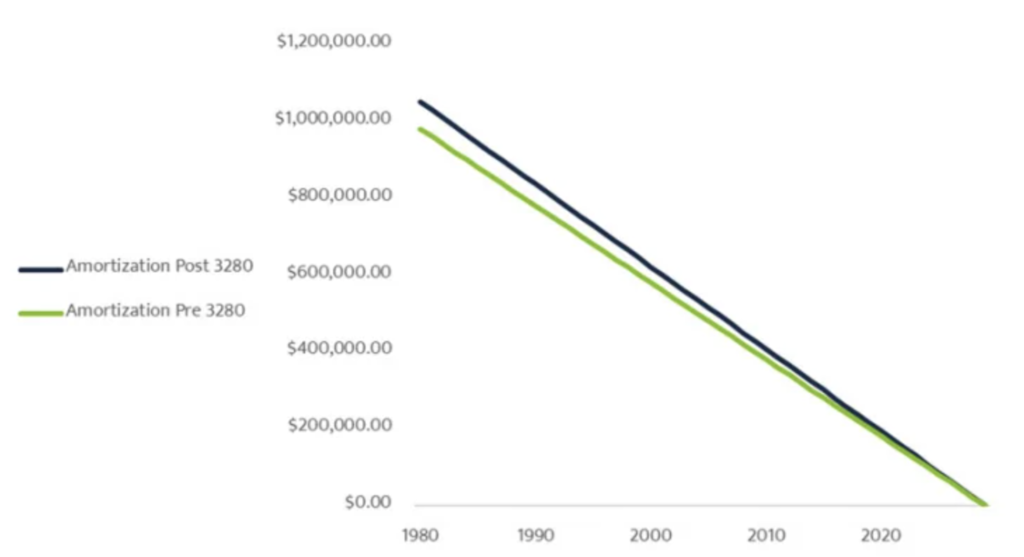

As a fictional example, ‘Local Government A’ owns a building it constructed in 1980 that has asbestos as insulation. At the time, it cost the local government $1 million to construct the building and the estimated useful life of the asset was 50 years. Using a straight-line amortization method, the local government would amortize the building at $20,000 per year for the life of the asset. The local government has no intention of continuing to use the building at the end of its useful life and instead will retire the asset. This initial accounting does not provide a standardized method for the local government to identify or account for the cost of removing the asbestos as they are legally required to do, so in 2030 when the building reaches the end of its life, the local government is hit with an unanticipated bill of $195,000 for asbestos removal.*

With the new PS 3280 standard, there are two major things that local governments will do which make changes to the accounting and financial reporting.

This standard will improve the information provided to users of financial statements. For example, understanding the full cost of the TCA will assist in making decisions about purchasing or constructing such an asset.

Increase The TCA Value & Amortization Expense

The local government will be required to estimate the cost of asbestos removal in 1980s dollars and add that cost to the value of the building for incorporation into the amortization schedule.

Figure 1. Example of increased TCA Value and Amortization Schedule

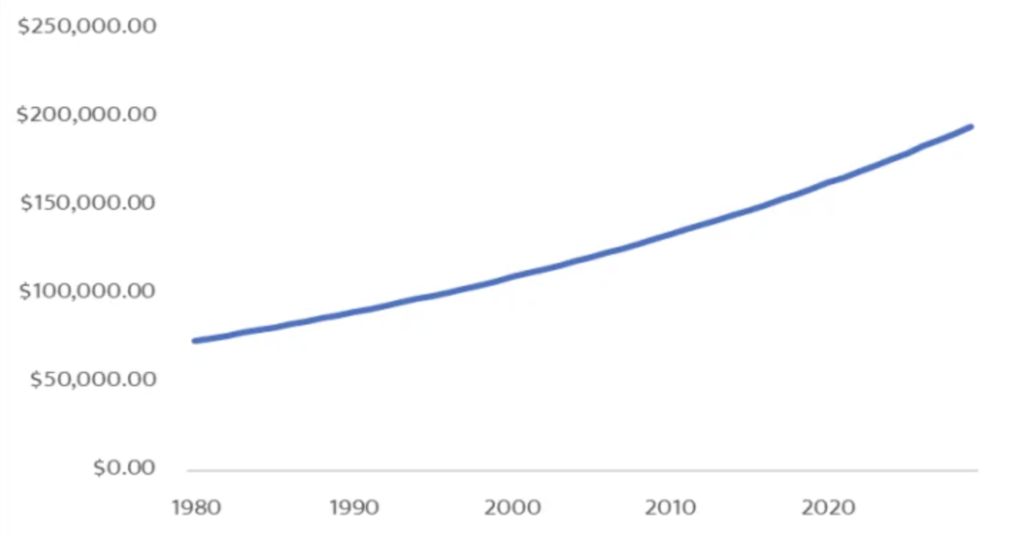

Add Asset Retirement Obligations & Accretion Schedule

At the same time, the local government would create an accretion schedule. In the future, governments may benefit from the Asset Retirement Obligations valuations because the accretion schedules could help inform the budget process of upcoming cash outlays related to asset retirements.**

Figure 2. Accretion Schedule of an ARO

PSAB Task Force Chair Kim MacPherson commented on the importance of the new standard as follows: “This standard will improve the information provided to users of financial statements. For example, understanding the full cost of the TCA will assist in making decisions about purchasing or constructing such an asset.” The more information local governments have to plan for future expenditures, the more accurate and effective their budgeting process can be. These activities can tremendously assist local governments in establishing and consistently maintaining reasonable and effective service levels across multiple years.

Difficulties in Adoption

While the example above may seem somewhat straightforward, many local governments will find challenges in properly adopting this newest standard. The challenges local governments face can be narrowed down into two categories: determining which assets require an ARO and what approach should be used to determine reasonable estimates of ARCs.

Which assets require Asset Retirement Obligations?

Determining which assets require Asset Retirement Obligations can be completed in a two-step process. First, a formal review of all contractual, legislative, or any other legal obligation requirements related to assets owned by the local government should be completed. The following flow chart can be used in determining if an asset requires an Asset Retirement Obligations:

Second, a best practice in determining which assets require an ARO was outlined in the Case Study: “Review & Restate TCA: Correcting Errors in Asset Data & Restating Financial Statements” from the September 2019 Issue of the Public Sector Digest. The case study highlighted the various benefits and advantages that can be realized from a full review of TCA data, such as increased confidence and better decision-making capabilities through improved accuracy within TCA financial data. Additionally, a full review of TCA financial data will allow for the opportunity to determine which assets may require an ARO.

Estimations

The most significant challenge for many local governments will be properly identifying the estimated costs associated with AROs. Larger local governments with access to significant funds can afford to hire professional assessment firms (for asbestos abatement, hazardous waste disposal, etc.) to determine the exact amounts required to retire all applicable assets owned by the local government. However, the requirement of the standard is to provide reasonable estimates for these costs, not necessarily exact costs. A more likely and easily standardized approach for the estimation of ARCs can be determined through advanced probability models that consider regional cost estimates and historical building standards. These estimates can only be used if the asset register data is accurate and complete. Therefore, local governments can potentially save money when hiring professional assessment firms through first performing a full asset register data review.

Budgeting for Asset Retirement Obligations

PS 3280 makes a significant step forward in the requirement to recognize the costs of asset retirement obligations prior to the time in which they occur. This standard will force local governments to estimate and account for these costs each year on their financial statements. However, the standard may be viewed as just an accounting exercise without links to financial planning. There is some concern that local governments, while understanding and accounting for these costs in their financial statements, may not incorporate these costs into their respective budgets in the near term.

There were similar concerns with PS 3150, yet, once local governments were able to understand and account for those costs in their financial statements, it provided enough impetus to integrate them into their financial plans. Over time, the development of the accretion schedules will provide local governments with enough information to both identify and budget for the liability for future ARO costs.

Conclusion

Achieving compliance for PS 3280 isn’t optional – this new standard is fast approaching, and regardless of the type or quantity of assets controlled by the government, there is work to be completed. Governments should start with an Asset Retirement Obligations Preparedness Report, post review of the entire TCA register. This provides a practical action for governments to take in order to better prepare themselves to account for the future costs related to the retirement of an asset. There is an opportunity for governments to learn a lot more about their assets, capture new and improved information, and document the necessary end-of-life costs (e.g. ARCs) while adopting PS 3280 and meeting the expectations of the auditors. Adopting PS 3280 will be challenging for many local governments; however, if done in a well-planned manner, there will be benefits and the process may make the adoption of this new standard a more worthwhile exercise than just another ‘accounting’ requirement to satisfy auditors.

* Values of asset retirement costs will vary across Canada and by type of asset, by a variety of factors.

** Accretion refers to an annual increasing amount related to the future liability, essentially the opposite of an amortization schedule.

WILLIAM KULSKA, MPP holds a honour’s bachelor’s degree in Economics from Acadia University and a master’s degree in Public Policy, focusing on economic policy, from the University of Calgary. In his current role, William produces regular case studies, applied research projects, and assists with client projects related to municipal budgeting and finance. His most recent projects include being a codeveloper of the GFOABC Budgeting Best Practices for BC Local Government Manual, and the lead analyst for the 2019 Geospatial Maturity Index under the PSD Benchmarking initiative.