News of the novel coronavirus swiftly reached Canadians by mid-January of this year. Concern sprouted shortly after Canada’s first confirmed case of COVID-19 appeared in Toronto on January 25th.

Throughout February, fear began to spread as the global market became more volatile and new cases of the virus were discovered in the provinces of Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec. By the first week of March, panic had settled in, initiating urgent responses from the federal and provincial governments. As March came to a close, cases have been found in every province and territory – except for Nunavut. The number of national cases has exceeded 8,000 and over 60 percent of cases are related to community transmission.

In response, the federal government has imposed new security measures to limit non-essential travel in and out of the country; encouraged Canadians to stay home and engage in “social distancing”; and released numerous new financial plans and programs to support industries, businesses, and residents impacted by the crisis. Provincial governments are declaring states of emergency or health emergency; preparing funding plans and programs; and imposing strict shutdowns of non-essential services. Municipal services, however, are widely deemed essential.

What is the municipal response to COVID-19? What can municipalities do to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 and support their local communities?

A Declaration for a State of Emergency

COVID-19 is a dangerous virus that is rapidly spreading by contact with contaminated surfaces or people and posing a significant threat to the lives of senior citizens and immunocompromised citizens. Immediate and severe responses are expected from our local leaders, but it is not always clear what is within their power.

To unleash certain powers and lessen the restraints on jurisdictional limits, provinces are declaring a state of emergency. Through a provincial civil protection and emergency management act, provinces may declare a state of emergency in the case that urgent action is needed to protect human life, health, or physical integrity. The declaration provides the province with the power to order the closure of public and private establishments, order the confinement of citizens, spend money without going through traditional avenues of approval, and many more measures to protect the well-being of residents.

A municipality can independently declare a state of emergency to enact the following types of measures within municipal jurisdictions as defined by the respective provincial municipal act: control access to roads, grant exemptions or authorizations to certain areas, make expenditures and contracts without going through the traditional avenues of approval, and other measures within municipal jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, provinces maintain ultimate control because they typically hold the power to conclude a state of emergency declared by a municipality. In British Columbia, the act specifies that a declaration of a state of emergency by the province overrules a local declaration, which ceases to have any force or effect.

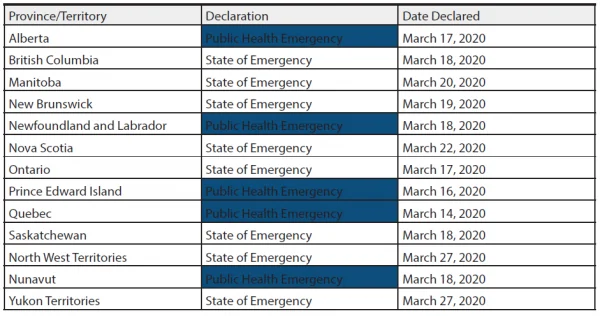

As described above, similar regulations with varying details exist across the country as seen in Ontario’s Emergency Management and Civil Protection Act, Quebec’s Civil Protection Act, and British Columbia’s Emergency Program Act. Declarations of a state of emergency often have a period limit, requiring that the province and/or its legislature renew the declaration if the emergency persists. Provinces have not allowed the declarations to expire, for example, Ontario has already announced the extension of the state of emergency for another 14 days. Table 1 charts provincial and territorial declarations as of March 31st, 2020.

A state of health emergency is not quite the same as a state of emergency. For the provinces and territories of Alberta, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nunavut, Prince Edward Island, and Quebec, the declaration emerges from their respective public health and promotion acts. The declaration sends the same message to citizens within the jurisdiction and enacts similar powers.

In Quebec, the Public Health Act allows measures to be taken without delay and without further formality, such as closing educational institutions, spending money, and requiring the assistance of any government department or body. The Public Health and Promotion Act in Newfoundland and Labrador gives health officials the authority to restrict citizens’ rights; the health minister in the province required the closure of gyms, cinemas, and bars among other venues.

Several municipalities that have also declared a state of emergency include, but is not limited to: Windsor, Ottawa, and Toronto in Ontario; Calgary and Edmonton in Alberta; Vancouver in British Columbia; and Montréal in Quebec. The circumstances are fluid as the spread of the virus persists and new information arises. Government responses are continuously evolving to keep residents safe and preserve the economy.

Table 1. Provincial and Territorial Declarations

Mitigating the Spread of COVID-19

With or without a declaration of a local state of emergency, the provincial or territorial declarations support a wide range of initiatives at the municipal level. Municipalities have ordered the closure of numerous establishments and the cancellation or reduction of a number of services. Across all essential sectors, employees are required to work from home when possible to protect their health and mitigate the spread of COVID-19. In many cases, closures and reduced services are based on the order to reduce physical human contact and maintain gatherings to below 50 or even 5 people.

In an effort to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 on human health and the economy, municipalities are closing numerous locations and discontinuing or reducing a wide range of services. In addition to closing or restricting public access to the town hall, municipal parks and playgrounds, recreation centers, and museums are closing.

In addition to restricting access to public spaces and buildings, municipalities are trying to flatten the curve – stop the exponential spread of COVID-19 – by cancelling or reducing services and events. In most municipalities, services and municipal conferences have continued but public access has been partially or entirely restricted, this is often the case with animal services and the town hall meetings. Other services have been cancelled altogether such as court services, parking enforcement, and public consultations for city planning. Nonetheless, there is a continuation of essential services such as the treatment and supply of water, garbage collection, and public transit in most major urban centers.

Financial Support for Residents

Further measures are being taken to lessen the financial burden on residents. A survey found that 44 percent of Canadian households have experienced reduced hours or job losses and the unemployment rate is projected to reach the highest level since the Second World War. In light of these changes, municipalities are looking for ways to delay or cancel certain fees for residents. Municipalities have taken some of the following measures: municipal tax payments are deferred for residents and businesses, as seen in many Quebec, Alberta, and Nova Scotia municipalities; transit authorities are no longer accepting payments to protect the health of their staff; and library fees are cancelled.

Some municipalities are also supporting the development of financial aid programs for residents or local businesses that are impacted by the spread of COVID-19 and the resulting economic consequences. Some examples include:

- $1.1 million is made available through a special local investment grant for local businesses impacted by the COVID-19 crisis in Trois-Rivieres, QC.

- A multi-sector partnership in Vancouver has released the Community Response Fund to deploy relief to not-for-profit organizations impacted by the pandemic that provide essential services.

- Cape Breton’s Municipal Grants Program, also known as the Sustainability Fund, has extended the deadline for applications to April 30th..

These deferred or canceled fees will take a toll on municipal revenue. To prepare for the inevitable financial setbacks, municipalities are advised to move forward with financial reporting as planned when possible, perform a procurement and reserve policy to help determine any changes that need to be made to prevent cash flow issues, invest in IT infrastructure to enable employees to work from home, and review the 2020 municipal budget if possible to allow for consideration of these potential difficulties

To prepare for the inevitable financial setbacks, municipalities are advised to move forward with financial reporting as planned when possible, perform a procurement and reserve policy to help determine any changes that need to be made to prevent cash flow issues, invest in IT infrastructure to enable employees to work from home, and review the 2020 municipal budget if possible to allow for consideration of these potential difficulties.

Connecting Local Leaders with New Tools

A new tool has been developed to connect Canadian local leaders. The Canadian Urban Institute (CUI) launched CityWatch Canada, an online platform that tracks local government response measures to COVID-19 across Canada. Through a collaborative approach, researchers from all over the country – including PSD’s research team – are contributing daily updates on municipal actions as it relates to COVID-19.

For 30 years, the Canadian Urban Institute has acted as a national platform to support collaboration and knowledge sharing amongst policymakers, urban professionals, business leaders, community activists, and academics. Through research, engagement, and storytelling, CUI aims to connect the country horizontally to discover the best approaches for healthy urban development. The President and CEO of the Canadian Urban Institute, Mary Rowe noted that CUI’s “two organizing principles have been around resilience and livability and of course both are being challenged extraordinarily under current circumstances.”

Municipal staff is often overwhelmed with limited budgets and the delivery of a wide range of services. In the face of COVID-19, a reduced workforce is required to maintain levels of service and provide additional support to the community. CityWatch will evolve in response to the developing circumstances to equip local leaders with the information they need.

At the time of the platform’s initial launch, the website will provide a comprehensive list of municipal responses such as, whether a municipality or their provincial government has declared a state of emergency, the status of municipal establishments, the impact on local governance, and the availability of financial support for residents, businesses, and municipal employees.

CityWatch was created alongside a companion platform called CityShare. CityShare is a tool populated with publicly sourced information to showcase examples of innovation at the local level by residents, community groups, and businesses. Daniel Bitonti, the communications consultant with CUI, emphasized that “both platforms are about fostering community resilience.” Throughout the COVID-19 crisis, remarkable initiatives by municipal governments and active residents are taking place, proving the advantage of strong community resilience.

Canadian residents and government leaders are faced with unprecedented circumstances. Communities require the continuation of essential services and additionally depend on municipalities to mitigate the impacts of COVID-19 and the resulting economic consequences. However, in times like these, communities also depend on human compliance of local response measures and human kindness.

ERIN ORR, MA completed her master’s degree with Western University in Political Science, specializing in Canadian Policy and she is completing a certificate in Climate Change Policy and Practice from University of Toronto’s School of Continuing Studies. Erin led the research for a case study series on the integration of climate change and asset management in Canadian local governments in collaboration with CWN, CWWA, and FCM.