Recently the City of Colwood was recognized with the award for Excellence in Asset Management from the Union of BC Municipalities for its Sustainable Infrastructure Replacement Plan. The plan is better described as a funding strategy than an asset management plan. However, our role as financial officers to secure long-term funding is the key to empowering professionals to engage in robust asset management.

An asset management plan bridges two detail-oriented professions: accounting and engineering. Both professions are known for an intolerance for inaccuracy. The fear of inaccuracy often leads to indecisiveness, therefore, resulting in ineffective asset management progress. Organizations are hesitant to begin asset management until all assets are remeasured, revalued, assigned a GIS location, inputted into sophisticated software, and modeled by costly consultants.

To further complicate matters, accountants and engineers can often be ineffective cross-departmental communicators. They report the often irrelevant (but accurate) accumulated infrastructure funding deficit that has now been calculated by sophisticated software. The financial magnitude is enough to elicit a sense of hopelessness at the Council table and with the public.

Colwood was determined not to err in the same way. We accepted that our estimates will inevitably be imperfect, but imperfection would be better than inaction.

We agreed on three broad steps:

- Fund first, manage second

- Present a palatable solution

- Eliminate unsustainable practices

Imperfection is better than inaction: Our forecasts indicate that adjusting variables and assumptions do not change the plan’s conclusions. Colwood forecasted $427M in capital spending from 2019 – 2068. At current funding levels, Colwood would only set aside 98M (or $285M with modest annual budget increases). This would result in a cumulative funding gap of between $142M – 329M, forcing the City to eliminate some capital services and take on significant debt. Supposing spending forecasts were adjusted by $50M, the plan’s conclusions would not change.

Put another way, the Sustainable Infrastructure Replacement Plan recommends setting aside $4.9M in annual funding. Annual funding in 2018 was $2.0M. Even if revised forecasts recommended annual funding of $3.5M, the plan’s conclusions would not change: there was a need to increase annual capital funding.

Fund first, manage second: engineers, accountants, and councils should be able to overcome their discomfort with imperfection with a commitment to refine forecasts in the future. However, the sooner that a local government improves annual funding, the sooner the engineers are empowered to prepare refined and strategic capital spending plans. Indecision is costly because organizations that are not funding sustainably get further behind every year. Engineers use available funding to spend reactively instead of proactively. At Colwood we have secured long-term funding first so that we can begin to address asset management sooner.

Present a palatable solution: Often I hear professionals describe the “infrastructure deficit” that exists in their community. This has become a cliché and fails to persuade public or policy makers. Most communities do not have an infrastructure deficit – their infrastructure is not failing and is not in need of immediate repair. Colwood’s sanitary sewer system is relatively new, for instance. The oldest PVC pipe is 30 years old and has a life expectancy of an additional 50 – 90 years. Accordingly, it would be an ineffective communication strategy for the City to claim that this infrastructure is at critical risk.

Nonetheless, Colwood does have an infrastructure funding deficit. Our assets will inevitably need to be replaced. The City can choose to save money gradually (and less painfully) over the life of the assets, or fund via debt and steep tax increases in the future.

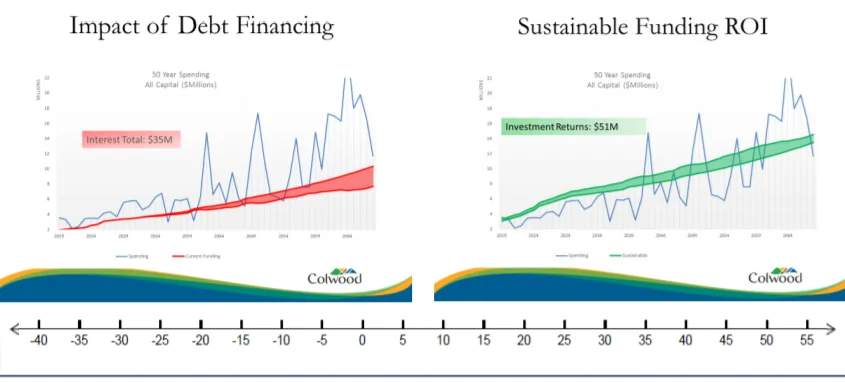

The Sustainable Infrastructure Replacement Plan demonstrated the impact of the two options:

- Option 1: fund sustainably and generate $51M in investment returns to complement funding, or

- Option 2: fund with debt and pay $35M in interest.

Colwood’s plan required 12 years of 1% tax increases to reach sustainable infrastructure funding levels. This amounted to a $25 tax increase to an average residential property each year for 12 years. This information was received well by the general public. A $25 annual increase sounds much less daunting than a $265M cumulative funding deficit.

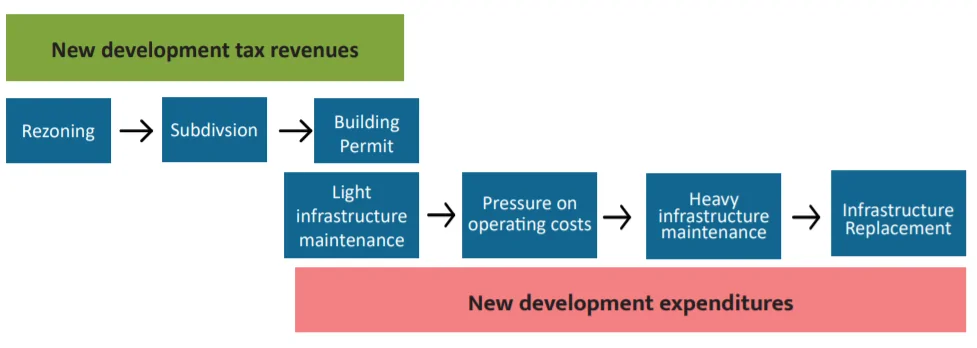

Eliminate unsustainable practices: There are systemic reasons why most local governments do no fund asset replacement sustainably. Most reasons relate to growth. Development results in increased tax revenues. At the rezoning and/or subdivision stage, land becomes more valuable. This immediately creates new tax revenue, referred to as ‘non-market change’ revenue. Finance professionals often use this new revenue to reduce the financial impact on existing taxpayers.

Inevitably new development creates new expenditures. These expenditures are normally incurred long after the initial non-market change revenue windfall. Developers build the infrastructure necessary to service the development. This infrastructure is donated to the City, creating a maintenance and replacement obligation.

Initially, maintenance costs are light, but grow as infrastructure wears. Infrastructure replacement costs are not incurred for decades. Thus, there is a strong disconnect between new development tax revenues and new development infrastructure expenditures.

Responsible local government finance professionals should endeavour to connect new development tax revenues with new development expenditures as best as possible. This strategy avoids intergenerational inequity and moderates volatile tax increases. At the very least, finance professionals should attempt to demonstrate the financial impact of continuing to allow such a disconnect to exist.

Whether new development tax revenues will offset or overcome new development expenditures is subject to significant debate. Furthermore, such analysis is land-use-decision-specific. Incremental costs are often indirect and difficult to quantify. For instance, a local government may ask how much additional police funding is required as a result of a new development. Are there economies of scale that result from new development?

…there is a strong disconnect between new development tax revenues and new development infrastructure expenditures.

Recently, the City of Campbell River attempted this analysis:

These issues bring another professional discipline into the mix: urban planning. Planners, whether or not they are aware of this, are asset managers. The decisions and recommendations taken by planners will have far-reaching consequences in terms of future infrastructure financing. Traditionally, planners have thought in terms of things like connectivity, access to parks and transit, urban design, integrating commercial nodes into residential areas, and tailoring permitted uses and densities accordingly. More recently, factors such as climate change resiliency, energy efficiency, local food systems, health outcomes and social justice play into evaluating what development should go where. Infrastructure, however, is often taken somewhat for granted.

Humans are great future discounters. The infrastructure component of the development is usually looked at in the here-and-now, with the assumption that the developer will pay to put in whatever is necessary, development cost charges will mop up any offsite upgrades needed, and the tax/user fee revenue thereafter will cover the maintenance. Job done. But not all pipes are created equal and new development plugs into a complex system. What is almost never accounted for at this stage, is the eventual replacement of the infrastructure.

To understand these issues better, the City of Campbell River recently partnered with the Province of BC to analyze potential development scenarios using the Province’s Community Lifecycle Infrastructure Costing (CLIC) tool. This tool allows a user to model a development concept at almost any scale, inputting the associated development typologies and densities, types and lengths of roads, sanitary and water lines and stormwater infrastructure. One can go further and model fire coverage, school place demands, policing requirements and carbon emissions associated with likely vehicle trip generation. Using standardized costing and lifecycle assumptions for these different elements, including future taxation and user fee revenues, the tool provides outputs to estimate:

- Initial cost to install/upgrade all relevant infrastructure,

- Annual ongoing operational and maintenance costs, and

- Annualized costs of replacing outworn infrastructure at a variety of future times.

Boiling down a complex package of individual infrastructure items into a simple graph tells a compelling story. It provides an at-a-glance analysis of whether development is truly paying its way in the long term and allows for side-by-side comparison of different development concepts, or even the same development concept conceived in different locations. We learned that development under current day conditions in Campbell River is far from cost-neutral to the public purse. Results are preliminary and a number of big assumptions had to be made in some inputs, but in most development scenarios the tool showed that annual tax/user fee yield just about covered the annual operation and maintenance cost but did nothing to cover the ultimate replacement cost.

This is the all-important L-is-for-Lifecycle component of the CLIC tool. In other words, once the infrastructure associated with development has been completed to the standards prescribed in City bylaws and handed over to the City, a deficit immediately begins to accrue. Once tax bills are settled and the business of the City completed for another year, there’s nothing left to put aside for replacing those assets. By playing with the model and cranking up densities of our hypothetical development concepts, we were able to improve that financial balance, although surprisingly high densities were needed to make it cost-neutral. By moving our development scenarios into more central locations with proximity to sewage and water and simple stormwater solutions, we were able to improve the balance further. But balancing the numbers to the extent where financial “sustainability” could be claimed proved very hard indeed.

Playing with this tool was invaluable for planners in understanding the asset management implications of their recommendations and policies. Good planning should always lead the way, but it cannot be conducted in isolation from the physical and financial realities imposed by geography and local circumstance. Similarly, the outputs of the tool can be of great use to finance departments, who can use it to model changes to taxes and user fees and try to match financial policy to land use policy. Each must inform the other and the biggest lesson learned from the project was the importance of having all your municipal functions represented at the asset management table and understanding each other.

Campbell River is not an isolated example. Often local governments that conduct this analysis find that new development tax revenues do not offset all direct and indirect new development expenses. The reasons for this are closely linked to infrastructure funding. The City of Colwood is proposing twelve consecutive years of 1 percent tax increases to close the infrastructure funding gap. In other words, the City’s tax rates are 12 percent lower than sustainable levels. Since rates are artificially low, new development tax revenue struggles to offset new development expenses.

The City of Colwood has adopted policy with the objective of eliminating the disconnect between new development tax revenues and new development expenditures:

- Use new development taxation revenue to offset incremental infrastructure life-cycle costs,

- Use excess new development taxation revenue to increase transfers to reserve until the infrastructure deficit funding gap is closed,

- Integrate full life-cycle funding into the City’s financial plan when assets are donated to the City, and

- Convert debt servicing budgets into infrastructure replacement funding when debt is retired.

These four policies alone will significantly improve the City’s future financial resilience. New development taxation revenue is set aside and reserved for related new development expenditures.

There was significant development in 2019 in Colwood. Early projections indicate that new development taxation revenue could be significant enough to pass on a 4 percent decrease to existing taxpayers. Given that significant new expenditures will follow in the years to come, this would not be financially sustainable. By contrast, staff will recommend that the new development taxation revenue be set aside. For instance, one of the developments will soon be donating a large park to the City that will require ongoing maintenance estimated to be approximately $200,000 annually. Other incremental costs will include additional policing, fire services, road maintenance, sewer maintenance, boulevard maintenance, sidewalk maintenance, storm sewer maintenance, and long-term infrastructure replacement costs.

Ultimately, the policy decision as to when infrastructure is funded should remain with our venerable politicians. Staff can no longer ignore their obligation to demonstrate the long-term impact of funding decision and indecision.

CHRISTOPHER PAINE is the Director of Financial Services and CFO for the District of Oak Bay. He is a Chartered Professional Accountant with over 10 years experience in local government. Christopher has worked in a variety of roles including the CFO for the City of Colwood, the Manager of Revenue for the City of Victoria and Manager of Finance for the District of Central Saanich. Christopher has worked closely with the Government Finance Officers Association of BC for many years and is also a member of the Municipal Finance Authority’s Pooled Funds Advisory Committee. Christopher believes local government financial professionals have a unique opportunity to learn from each other and share experience. Anyone should feel welcome to reach out to him any time at [email protected].

CHRIS OSBORNE is the Supervisor of Long Range Planning at the City of Campbell River and a chartered member of both the Royal Town Planning Institute and the Planning Institute of BC. Chris has over 13 years’ experience in municipal planning with time spent equally between long-range planning and current development planning. He holds a Masters in Planning from London South Bank University, in addition to a Masters in Nuclear Astrophysics from the University of Surrey.